Sylvia Peck

Sylvia Peck was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, but spent her first decade in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Sylvia is a published novelist and poet. She graduated from Clark University, and obtained her law degree at the University of San Diego School of Law in San Diego, California. She practiced law in New York and Massachusetts, first as a Federal Defender in the Appellate Bureau of the Legal Aid Society in New York, NY, and later as counsel for the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection in Boston, Massachusetts. She taught legal research and writing at Suffolk University School of Law for several years. She also taught a course in Children’s Literature at Emerson College.

Books

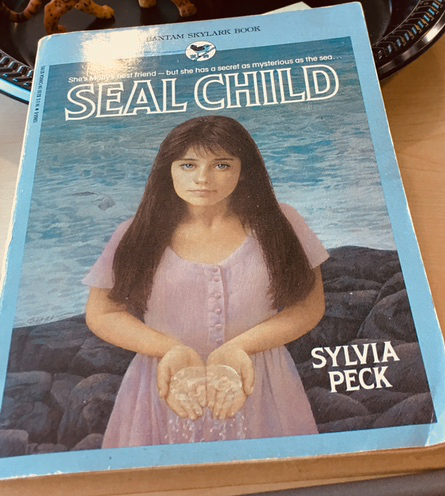

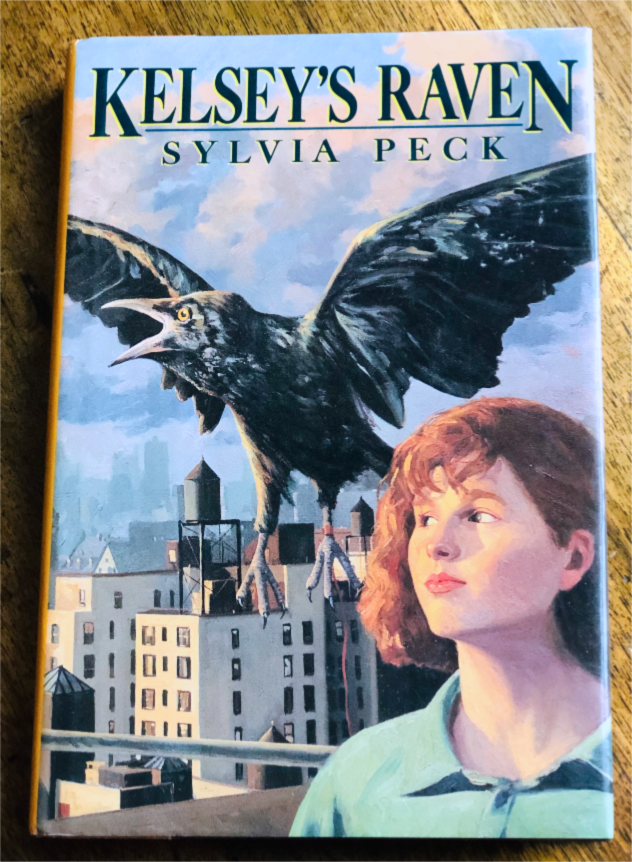

Sylvia Peck is the author of two children’s books: SEAL CHILD, an illustrated middle grade reader and KELSEY’S RAVEN, a young adult novel.

(Morrow Junior 1989, 1992, respectively.)

Bantam Skylark brought SEAL CHILD out in paperback in 1991.

Sylvia is nearing completion of her current project, GHOSTHOUSE, a catwalk of a ghost story set in Provincetown, Massachusetts, where she makes her home.

Several chapters are available.

Poetry

Worm Moon

Ten years of marriage

guarantees a widow’s tithe.

Ten, twenty, thirty years

before your bent groom stumbles under the scythe, your pittance is secured by the state.

Marriage, being

so bland a tenancy

auditions are obsolete.

A living man may, upon his death, sport two widows, or three or four, so long as each has wielded at minimum, a constant decade.

I’ll be the one walking the west end at dusk, with a spaniel.

The last time I let my husband visit, our cherry tree was a mass of green foliage, and the undergrowth was strewn with pink blooms.

He said he’d thought long and hard about confessing the actual name of the woman he was living with, as it went against his better judgement. Perhaps he didn’t quite trust me.

Though he stuck his landing—a crow among wrens — and announced— all else being equal — that he would prefer not to lie.

I held my face at bay.

—For emphasis, he added: “I mean to get it right this time.”

Even his last words were slippery thin, pale as camellias, splashing tall shadows over a quarter century of my pretending

I didn’t mind he’d picked me, for contrast, because my face told the truth—

© Sylvia Peck 2020

Prayer to Canyons

While traveling, I heard mention of Kyoto, with its golden temple, and its many stairs. I fought for an image but could not tell if the stairs led up or down, though the heat in October decanted memory. Movie scenes crowded in with Uma Thurman climbing toward some Zen Aikido master, carrying pails of water, though I could not tell if she walked the stone steps up or down.

The death knell of marriage beat in my throat, as it had earlier in the decade, timed as my metabolism stormed haywire, though at the time I thought I might be loved in sickness as in health and so felt no real terror when doctors pressed fingers to my neck to gauge the pulse at my aorta — not unlike a fluttering below the chin like the thrum of wings. I loved this. So very "Green Mansions"; so Rima bird girl —

I thought of Kyoto later that evening, as clouds moved in, and the forecast of rain made me hope for blooms in the desert, though I knew I was mistaken. I imagined kimonos ascending, descending in cloud cover, like wheels of fabric, blind as silkworms, loving the mulberry, the waving green leaves.

I had to bite down, I had to grind teeth not to say — Oh, I know someone who loved Japan, who longed to bring me to Japan, to Kyoto; its golden temple a trip we would make someday, once we had earned the time. My marriage tolling in that fog, a warning not to dwell on better days.

I want to say that the forsaking of those dreams, the ripping out of the threads of the embroidery of those dreams, leaves me without stars, only the blue-black expanse of heaven. To forsake my marriage was as though the very island of Japan — Kyoto — began to sink. And I knew it was my decision to sink her; my conviction the suck of a great downspout until only a scattering remained, like tattered sails; bereft, treading water, under a blue and starless sky.

As dawn rises nearer the Pacific than I have been in decades I have to turn the prow of this poem myself. It is so hard to trust. It is so deep within me to trust no one — the iron filings of conviction flung down toward the jawbone that clamps teeth until my prow glides forward, silent, parting constellations. I focus on the horizon, on the mauve clouds of a silken kimono on a silvered hanger — a gift I might display again and again on future days, or in some gypsy caravan as the Tinker of the Steppes I will most probably remain until I die—

Forever now, I remember thirst and hunger and sweat and dust; the stamping of hooves in Ranchita. I remember horses in their corral. I imagine them in the darkness, contemplating the sweet, cavernous pledge of night. I count them: the bay, the blaze, the mare, the mustang, the Appaloosa, romping and blowing in the chill fog and rain. I remember hoping white sun would blaze through and when it did I turned my face upward thinking you fill me with dawn. Head flung back and ageless—You fill me with dawn.

© Sylvia Peck 2021

Silver Horse Ranch, Ranchita

Chapter One

GHOSTHOUSE

The house is surrounded with a black chain link fence and a huge padlock so no one gets in or out; and still, every night, a blue light comes on in the tower. There’s a sort of a widow’s walk around the tower, painted white, like the house, but the whole thing has gotten gray along the posts and railings, like something left in an attic. The blue light is suspended, hung down from a piece of electrical wire. From the street, you can see how unevenly the wire is strung there, like bait. And it never burns out —just stares at you, like something very sad that a grownup would never notice. Or something so sad that a person, running their fastest, wouldn't notice either. You had to have another person right there to catch you by the shirt and grab on and make you stand there; looking up really hard. For me, that someone was Gabe.

The Captain's house was set back from the sidewalk, at least 50 feet, making it look sort of grand from the time of sea captains and whalers; and probably, like my mom said, this was once some captain's house. Before the chain link fence and the padlock, before a lot of other stuff like cars and cobblestone pavements and the view to the water blocked out by the whole waterfront deal, you could see a lot more. Through the fence that separated the Captain's house from its neighbors, you could see a pair of greenish-white lion statues the size of Great Danes, crouched at attention; the kind of things a rich sea captain might have brought back from China. From where Gabe and I stood, you couldn't tell if the green was moss or actual veins of jade, but my mom once told me she didn’t think it would be jade. I know about jade from her taste in jewelry but that's another story.

I’d gotten into the habit of running past the house, if I happened to be out and about, after dark; so that by the time dusk hit and that blue light started to glow, I’d be racing myself home. It had to be a very sunny day for me to think about what made me want to stare — a blue sky kind of day. Then I’d make my list of curiosities: how that light was turned off in the daytime; how no one lived there to turn it off or on; how I’d asked the oldest person I knew in town in case she remembered from way back and she offered that maybe the light was kept on up there so planes wouldn’t crash into the tops of houses.

Sounded like a really dumb answer to me, but I didn’t show her anything except courtesy on account of my mom. I mean, maybe there was a logical explanation - maybe someone had put the light on a timer, so that it would go off and on at certain times, the way people did when they went on a trip but wanted robbers to think they were at home— but that didn’t really make sense to me deep down.

Because, why a blue light? That’s what I wanted to know. It seemed like some sort of a message, even if I couldn’t get the whole meaning. So, of course, when Gabe came to stay, I showed him my way of running really fast past the deserted house, but he caught me by the back of my shirt and grabbed on. He made me stand there in front of the chain link fence, made me smell the honeysuckle that crowned it. He gave me a lift up - balancing my right foot on his two hands so my arms could grab the top of the fence. I told him every single thing I saw down to the rusty lawnmower, because Gabe had given me that job to do. His part was to make it possible, you know: plan it. My part was to do the smaller stuff, because I was shorter and lighter. I remember telling him there was a chair up in the widow’s walk, like the kind of empty chair you see in movies where somebody is going to ask somebody else a lot of tricky questions. Only in those movies it's a very bright white light, and this one was blue. As in, ghostly.

When Gabe first saw it, he said it made him think of Louisa. When I asked him why, he said: her eyes.

Louisa was Gabe’s sister and she was drowned five years ago even though nobody told me for a long time because they didn’t want to scare me. That makes her my cousin, along with Gabe, who is my cousin. Gabe and Louisa, are Dulleses and I’m a Dulles, too. Boyce Andrews Dulles. I’ll be twelve years old this November which is younger than Gabe, and both of us are older than Louisa because she died when she was six and I don't think you get any older after that.

I’ll tell you right off I know Boyce is a dumb name. The truth is, the town of Boyce is a little place in Alabama that my parents drove through and liked. So that’s what they named me, even though most Dulleses don’t live down south any more. Dulles is my mom’s maiden name so she made sure I had it. As for the Dulles part, I’ve heard it all, and we are not dull, dumb, or stupid, but actually mean tough fighters, especially the two of us together. That would be me and Gabe.

Gabe comes to visit almost every summer, and this summer was no different, except that way up front his parents told us that it would be a shorter spell - only the months of June and July. Which was fine. They had him going to some new school in Texas that started early. Plus it was ninth grade and all, because they’d started Gabe up ahead or something.

Gabe likes Texas okay. He brags a lot about the snakes down there for one thing. The rattlers and the hogs. You have to get him real still and quiet, for him to tell you any different. Tell you he never saw a wild hog; no rattler, nothing like that. No horror of the natural world.

That first night I showed Gabe the blue light, when he gave me a leg up and I hooked my fingers into the black iron of the fence -- that was just the start. I remember it seemed possible, with Gabe there, that the two of us could scale that fence, if we waited until the dark felt right, because it was just a house, right? Just sitting there begging us to visit. Making sure that blue light was on.

Meanwhile, I had the highest view I’d ever had of the lawn and the grounds. I noticed more: how freshly mown the grass looked; how all the window shades were drawn. I could hear Gabe complaining that I was getting heavy and also that somebody might come, but I swear I loved it up there: the scent of the air was like wisteria or some old flowery perfume.

“Wait,” I hissed. “Wait a minute.”

“Easy for you to say.” Gabe shifted his weight under me and I lurched forward. The chain link was too small for me to get a good grip, and my other shoe was sort of clawing at it for a foothold.

“I mean it,” I said, and I tried to make sure my top foot found a place, which didn’t help at all because Gabe was just gone. In fact I could hear him running away from me which didn’t make sense. Then I fell. From the pavement I could see much better what the problem was and how Gabe had gone to meet it.

Billy Nuss was there and Zander Norton, alongside, zooming toward us on skateboards. I noticed a couple of their wannabe girlfriends strolling up and stopping by someone's parked car and just standing around looking nervous. I knew this was bound to be trouble because Zander and Gabe had sort of crossed swords before.

“If it isn’t Gabriel—” said Zander. Gabe hates anyone to use his full name.

“Hey, Zander,” said Gabe.

“What happened to you, Boyce?” said Zander, ignoring him.

“I fell.” I had to say something because my elbow was skinned, along with my ankle, and bright red blood kept welling. I had to keep wiping the blood off with the bottom of my shirt.

“Don’t you know that house is private property?” Zander’s Dad was a lawyer.

“So?” I said. “Nobody lives there.”

“It’s in probate,” said Zander.

“You don’t know that,” I said. One of the girls laughed. The blonde one. They were such harpies, girls. They always laughed if they smelled blood.

“Bet you don’t know what 'probate' means,” said Zander.

“I do,” said Gabe.

“Well, who asked you? Who says probate is the same thing in Texas as it is here?” Zander pronounced it TEX-ASS. He did a half spin on his skateboard and the same girl giggled again. “Anyway, probate means someone’s fighting over it and it’s worth a lot.”

“I knew that,” I said.

“My Dad’s handling it,” said Zander.

I grabbed Zander's arm. "Do you know why there’s that blue light on upstairs? – I mean if nobody lives there?” I felt the blood trickle down my elbow, land on the back of my foot and trail down my heel.

“Never thought about it,” he said.

Gabe started pulling at me to leave but I hated Zander for bragging and then not even knowing anything for sure. “Well, then, you don’t know anything that counts,” I said.

“Oh, you do, Boycie?” I hate anyone to call me Boycie.

“Maybe not this second,” I said, “but me and Gabe are going to find out.”

“I could get you in so much trouble,” said Zander.

“I could get you in more trouble,” I said. That shut him up. Zander’s Dad is always wanting to date my mom, so I have sort of an inside track to be believed and Zander knew it. And if he didn’t know it yet, I’d make sure he learned so the hard way.

Also, although I hate to admit it, I am a girl. My mom says that being a girl counts double which in certain matters means it counts more.

“Dare you to get all the way inside the house, then,” said Zander. “You have 48 hours before I tell anyone.”

“Done,” I said.

"Forty-eight hours before the search parties drag out your bodies,” said Billy. As if Billy Nuss could scare roadkill. The blonde girl lit a cigarette and shared it with the other girl. They were passing it back and forth and not looking at anybody. Zander pushed off on his skateboard without a backward glance. The two of them just left the girls there; so me and Gabe did the same thing. We walked off and left them, on foot. I figured they were a bit older and probably just up for the weekend. Zander always had followers that way. His Dad gave him this huge allowance; so he got into the habit of buying pizza for anybody hanging around. New girls always thought it meant something. My mom said it meant money and that money has a very temporary effect: how money might make you popular for a while, but not much else. I’ll tell you another thing. Money was making me hate Zander.

We were pretty quiet walking back to the house, Gabe and I. Gabe knew asking Zander anything had been a mistake but he didn’t blame me for it. I liked that he didn’t say anything.

I hated Zander for teasing Gabe about his name and his accent and everything. I actually hated everything about Zander, come to think of it. I couldn’t see why my mom liked his Dad.

I let Gabe walk ahead of me, and looked hard at him to see how he’d grown. I measured myself against him that way. But where I seemed to be soft in ways I hated, Gabe was all bone. He was tall, besides, so that people always took him for older. I’m sure those new girls thought he was way past fourteen. You wouldn’t call him a skinny kid because he didn’t look gangly or awkward. He looked strong. People were always noticing him first. Things like that I’d attribute to his bones.

My mom always said that you could tell a lot about a person from their bone structure. She meant that you could observe a lot about about a person from their face, although she didn’t like to come out and say that because it would be like pointing. When I think about the way that people looked at Gabe, I think how everything about him, inside him, was shining.

There’s one thing about the summer that townies can’t forgive. Can you guess? No? Well, that would be the tourists. First off, they stare. Second, they dress funny, like from Omaha or someplace extremely ding dong, the witch is dead. Third, they block traffic. You know, because they stare.

It’s easy to block traffic in my town because it’s small and narrow and really has only two main streets. The street everybody walks along – especially in summer – because that’s where all the shops are and where everything happens – is called Commercial Street. My mom’s shop, for example, is on Commercial Street, in a storefront, transformed from the front parlor of a wooden house that probably floated over from before the Constitution. I don’t know why people stare. I mean, I do understand, in a way, but let’s just say I’ve never been anywhere where I thought two people holding hands in daylight was any of my business. When you grow up here, you sort of get used to anything – except that I still feel the pull to go all out and shock everyone into stupor.

The crickets were out when I heard Gabe outside my window. We shimmied the screen up and I clambered out backwards, feet first. This time I wore my tennis shoes with socks, though. The crickets were sawing, and there was dandelion fluff you could reach out and grab from thin air.

We chose to walk right down the middle of Commercial Street where enough light spills down from the street lamps that you can almost always see the asphalt spangle in front of you. You have to be alert, though. There are always potholes and you can still trip. You could come crashing down on a bike.

My ankle hurt and I think I had some sand or grit in by my toes. I smelled like sweat and dried blood, but I didn’t have time to do much more than take a fast sponge bath, because I didn’t want Mom to get all funny about bandaging me up. She had every size bandaid under the sun, and some gauze and adhesive tape from about World War II that she’d rip off with her teeth. She had ribbon and bobby pins and safety pins, and a real honest to goodness sewing basket. My mom could thread a needle faster than spit flies. She deserved a fancy pants kind of girl she could dress up in pale Victorian lace. But she drew me from the pack, and that was that.

Mom's hair is auburn, almost bronze — where mine is more coppery: Bright as rusty water in a bathtub, when the light hits just right. Mom runs a sort of vintage shop in town. She mostly sells estate jewelry and one or two curiosities, 'exquisite pieces', is what she’ll call them. So the seamstress thing comes in handy.

The moon was almost full, so Gabe didn't have to use his flashlight. We walked around the perimeter, which was kind of brambly, but no one was awake at that hour — which was good. I could see that the front door was padlocked. I snuck through between the sidings and the chain link fence to the back door. I tried the handle, but it was locked. The mosquitos were thick down low. I had to shift from leg to leg to brush them off my bare calves. The grasses were tall by the back cement steps. We must have been near standing water. The thunderstorms here can fill up anything overnight that doesn’t drain easily as sand.

Gabe vaulted over the corner fence and tried the front door. I heard him curse softly. I heard him sort of swish through the weeds. Then I stepped aside and he tried the back door knob himself. The door sprang open, as if attached to a pulley.

“Hey,” I said. “That door was locked a second ago.” But Gabe ignored me. He was already inside and bounding up the steps that led from the back door straight up. I could hear him clumping around overhead. Just then the hackles rose on the back of my neck. The kitchen grew cold — though when I glanced out the windows I saw no one, only my own reflection. Then I saw her. I shouted for Gabe. But I realized how futile this was, and how no one would believe me. So I grabbed up the first thing I saw from the old formica counter, a sugar canister, and heaved it forward, with two hands, like a pail of sand.

I heard the lid clatter to the floor and the sugar flew out and stuck. It lay Mother-of-Pearl translucent, glinting like cellophane wrap. For some reason I thought of night blooming bell flowers, or spires of roses flown in long stemmed white boxes. I knew at once this was a ghost of sorts, because draped there glimmering with sugar was the figure of a girl. But whether this ghost would hinder or help, I did not know.

No one spoke. We just stared at each other, without a sound. We were transfixed, the two of us. I couldn't move and hardly dared to breathe. I completely lost track of time until I remembered Gabe was upstairs doing the heavy lifting. I called out to him, and heard the scramble of his footsteps echoing above.

Gabe bounded down the kitchen stairs, two or three at a time, by the clumping, threw me a look and muttered "attic". Then he grinned. I figured there must be a trap door or something that he'd found by flashlight but we had no time left. We’d have to come back. As it was, we couldn't be sure of enough moonlight to find our way home through the dark alleys.

I heaved Gabe on his way; grabbing at the thickest part of his arm to show him the door. The ghost girl didn’t like that much. I felt her eyes on me by the way my spine seemed to burn and wither under her gaze. I spun round to glare back and declare Gabe off bounds, but she had already begun to shimmer and melt like the glaze of ice sliding in triangles off our front windshield.

Who are you? What are you? Silence. What's your name? I thought — What should I call you?

I heard a door slam somewhere and I ran upstairs after her as I would chase after a real girl. I almost slipped on the stairwell. I had to anchor myself on the bannister. I kicked my shoes off to move faster. The center of the stairs was carpeted, and I knew I was faster without them. Besides, while I didn't doubt my eyes, I didn't really believe in the supernatural. I was determined to make sense of whatever she was.

The heavy wooden doors were all locked to me, as the back door had been at first. I wished for Gabe's help, but he was probably halfway home. The third door sprang open almost before my fingers touched the doorknob to reveal a huge ballroom with a baby grand positioned by the tall front windows, so that two figures might play a duet of sorts, and watch white sails feather the bay. I looked out below onto a grove of sapling willows. Willows meant water, according to Gabe. I saw the lawn dip over stones to a dry creek bed that might flood come spring.

The ballroom stunned me in its gleam and polish, but my ghost was nowhere to be seen. The grand piano sat on a marble stage, raised only inches off the floor, but the floors were glossy, like polished ash. The room was begging for dancers. And yet nothing.

At least tell me your name, I taunted. So I know what to call you. I felt her ask me a question then. I felt her question burn in me like radiant heat. She was asking after Gabe. My cheeks flushed.

"Hands off", I said — but I thought worse. I thought of kicking the piano bench or scuffing the pale molding with my sneakers, until I remembered they lay at the bottom of the stairs. I can always make up a name for you. I glared my warning at that ghost, wherever she was.

And there, in a gleaming mirrored side panel, pale letters etched themselves, and faded,

but not before I'd read her name:

M-A-L-L-O-R-Y

Mallory Rose Hutchinson.

Whoop de doo, I twirled on my way out the front door. But of course the front door was padlocked from the outside. I looked back at her message: and Gabriel is mine. The words appeared in a rosy hue, like the tinge of an opening blossom. I wished fire on her willows, and a blight on her roses, peppering the front gate. I gathered this ghost liked getting the last word in. I slammed the door behind me. Because Gabe was mine.

Chapter Two

I'd first seen the group of them walking brick cobblestones near the scent of rosebuds and unripe berries and was seized with desire. It was a warm, humid night, and the breeze off the ocean was cool and felt as welcome to me as greening ivy along a brick wall in summer.

My name is Mallory Hutchinson and I am but fifteen years old. Old enough for jealousy and greed, and lies. Old enough for battle.

I will never be sure what pulled me back to the shadows, to eavesdrop on their bored flirtation— although even a whimper of flesh can make me crazy for sensation, for smell and sound and substance.

Without thinking, I kept apace, watching their weird flickering insults like flashes of heat lightning. They trailed bravado. I could not hear well, though I heard the name 'Gabe' often enough. I heard the redheaded girl shout for him in pain. Perhaps it was her anguish, that catch of pain in her cry that lured me from my icy depths where none breathe or cry out or make a sound discernible to human ears. I speak of that brackish deep I plunged, and the murky drop off where I could find no purchase, where nothing lay below my feet, as I tumbled ever into the burning ceaseless dark of dreams. I awoke to slick caverns of granite, cold caverns where I was buffeted and wedged, below the decks of my sleeping town, and her boardwalks and train tracks and curved streets and dunes; below all skies and clouds and storms, below the teeming tidal weeds, where baitfish sputter but neither girl nor child may draw breath.

Time enough to make a prettier story, to draw out for another gloaming twilight, how I woke and where; how desperate to mend my torn shift and petticoats, to wash myself clean of the stinking fish slime of my first death— which hung overhead like a possum.

Silence pulsed at first, in such flooded place as I found myself, without food or sea flesh or fresh water to cup. I had to take measure of the absence of thirst— as an indifferent fact, like the absence of rain come July.

But the absence of color was searing, and brought my slender mortal dread home to me, like the thud of an axe. Had I ever seen an oak tree felled? I think I had not, though who can say what I’ve heard or seen these centuries since dying?

Now, awakened, I watch as the oaken stump on the commons below blooms with bright moss. I watch and marvel as curls of pale lichen in olive & chartreuse begin to spawn and shelve like some stew of spring watercress set along a stove to marry.

I was moved to weep often over sheer memories — even the colors of the bay — all fathoms of water from her blue green shallows to her amber violet waves at dusk. I knew the harbor like the back of my hand. I'd spent my childhood along its wharfs. My father sailed those seas and I'd always wave from shore and bid him farewell till his ship rounded the curve toward open water.

I was but a maid when I drowned, my lungs suspended and lumpy as turned milk. Mortal death and the absence of even remembered color is the saddest future on earth, this dark earth I roam, in this sleep of sorts.

I mean to leave all such behind me and be done with it once and for all each evening as I pace to and fro, but I have not quit her yet, my ledge, nor this tall and starry landing.

I remember more. I remember calling out, first in piteous shrieks before I knew what name to shriek. Then I called for help. I called and called for anyone to come, to answer back, to befriend my very agony. Finally, I fell silent. There was no one within earshot, obviously. No one who might hear. It occurred to me I was dead. I’d shake off the thought, but it returned. And numb and patient as mussels, I waited and seethed.

At some point, out of that darkness, a stranger arrived on the tides. He called himself Ashton. We could speak somehow, or sense each other’s thoughts, though I never learned his surname. He seemed ancient enough, clad in a dark silk that clung to his form, but flattered him somehow. By low tide his clothes seemed to almost dry, and he would recount stories, though never those I asked for. Whenever I pestered him to learn of my Gabriel, or Gabe’s sister Polly, or the other girls, or even what they thought of me in whispers, or what the world thought of my misfortune — why, Ashton deflected each one of my questions. Finally, I fell silent. Didn’t Ashton insist I was not ready to know, was too weak to know; that I must first prove myself worthy to know?

As I said, Ashton appeared on one or another of what I call between tides, when fog could roll under the lip of the quartz overhand. Ashton placated me with instructions: Ashton, who taught me the power of haunting — of the name for what we are, those of us walking the places near our deaths as if to reverse catastrophe. I tell you here and now from this ancient place of beach and sandstone where lavender grows and scotch broom billows, I tell you I would have done anything to have Ashton return to me, for no other soul brushed mine in the darkness. From this outermost curve of Cape Cod, where swordfish leap and plovers pipe, where each September swallows feint and roost in great swarms, but few remain. Here, where I sentry, my hapless ears could make out no songbirds save jays and sparrows, and the ruby cardinals amid the holly. I’d look out at my beloved moors where the heron grazes and the kingfisher strikes, but saw no one search for me, ever. What else can I say?

Though perhaps it is a truer thing to say that I am myself the story, clad in salt and shadow and a skin that no longer reflects light, where bats fly in great herds at dusk trailing bloodlines of garnet, and no sun shines.

It was easy to sense what the redhead was thinking. Well, easy for me. Thoughts etch themselves on the wind like hoar frost or ice, and can be sensed for a long time afterwards. Lurking in mere ounces of hours.

We live by estimates, said Ashton. We seize the living, as it were. We calculate the number of weeks in attendance, as an inebriate might shake the dregs of a bottle of wine to estimate the time of night.

This young girl was proud, but troubled; bad news for a schemer, if scheme they meant to lay.

I’d listened intently as they bargained, but could not decipher from their petty bickering what exactly was meant to happen next. Nor was I easily able to decipher their humor alongside that great taproot of gender they straddled.

Those poor girls and the two quarreling boys made such a noisy crowd in a street already swollen with crowd. Though no one saw me, I made sure. We practice tradecraft like spies, and shed neither fear nor footprint. In the end, say I followed behind on a snare of my own making. Say I dared myself to remain aloof, to stare down fate; thwart their ridiculous wager. But I’d like to think it a purer impulse, visceral as blood, like the faint metallic taste of the side of the girl’s foot, seared on my iron gate.

My name is Mallory Hutchinson, and I am a Haunter.

© Sylvia Peck 2021

Contact

For all inquiries, Sylvia Peck can be reached by email at: